As we head towards the election on November 3, 2020, the question is not whether the US House of Representatives will remain in the hands of the Democrats. Polling suggests that is a near certainty. The question is by what margin they will control the chamber. Democrats currently control 232 seats, while Republicans control 197 seats, with one independent and five vacant seats. The number of seats controlled by Democrats in the 117th Congress has significant implications for Democrats’ ability to forward their agenda, especially if they are also in control of the White House and the US Senate.

Below we take a look at a few of the structural forces at play in the House elections and identify key races to watch on election night.

On election night 2016, Republicans controlled 241 seats in the House. The 2018 election went disastrously for Republicans as they lost control of the House for the first time since 2010. A Republican return to control two years later was always going to be an uphill battle. The last time a party regained control of the House a mere two years after losing it was in 1956 when Democrats retook the House.

House Republicans are going into the cycle with 31 of their members retiring. By comparison, Democrats have only 12 members retiring. The incumbency advantage in House races has traditionally been significant. With Republicans having to defend 31 open seats while trying to win back enough seats to retake the House, the proposition of a productive election night becomes all the more challenging.

Since the 1994 Republican takeover ended 40 years of Democratic rule of the House, we have seen three change elections: 2006, 2010 and 2018. A change election occurs when the minority party flips a significant number of seats previously held by the majority party. The challenge for the new majority party after winning a change election is to keep those seats from immediately flipping back to the other party in the next election. This is one of the key challenges that House Democrats face on November 3. In order to keep their majority, Democrats must hold seats that Republicans won in 2016 with Donald Trump at the top of the ticket.

Democrats are also attempting to expand the electoral playing field with competitive candidates in as many of the seats being vacated by retiring Republicans as possible. This will allow Democrats to potentially grow their majority.

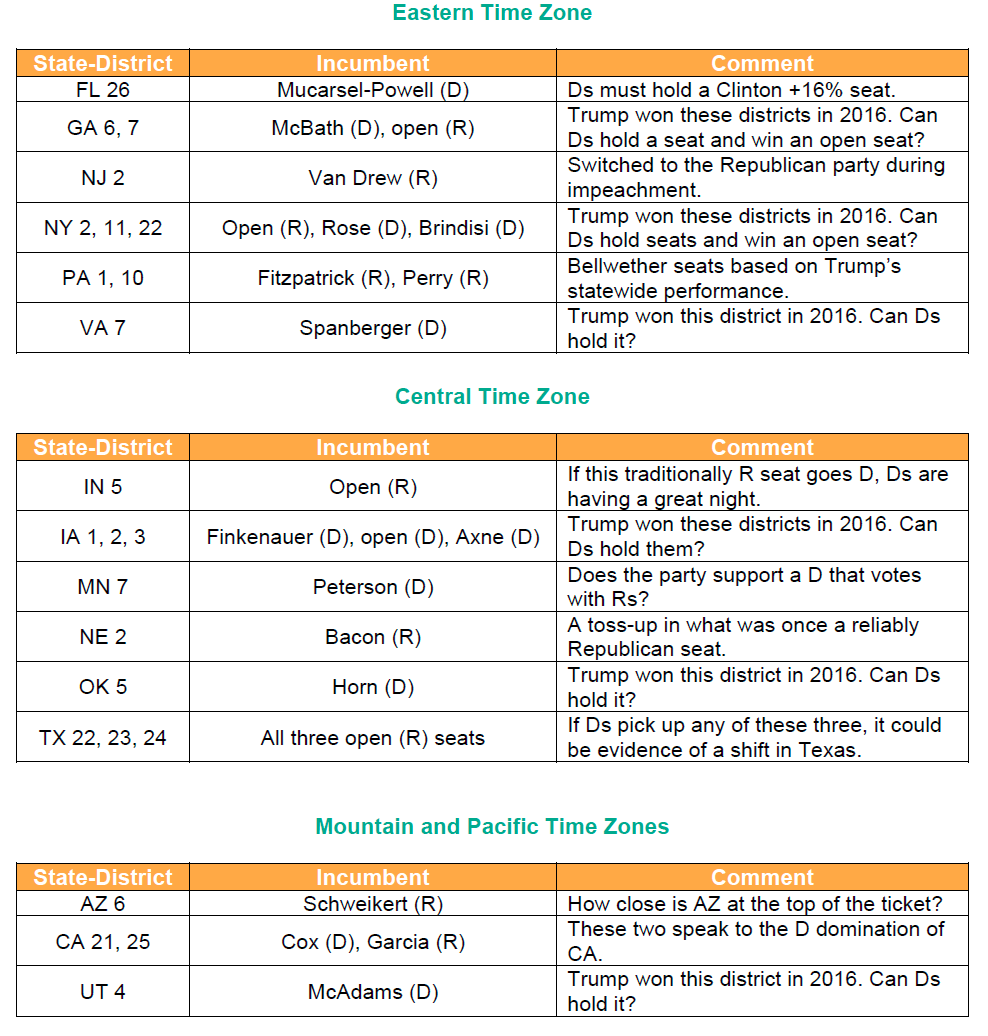

Below are 24 seats that will be important for deciding party control and margin in the House. They are currently evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans, 12 to 12. The charts below are divided by time zone for your convenience as you follow along on election night.

The Democratic seats are predominantly held by incumbents seeking reelection for the first time with President Trump at the top of the ticket. Democrats’ ability to hold these seats is critical to growing their margin in the House. If Democrats lose these seats while not picking up Republican seats, it will be a very bad night for the Democrats.

The Republican seats are a combination of incumbents seeking reelection and open seats. If Republicans lose these races in states such as California, Pennsylvania and New York, it may

be indicative of a defeat at the top of the ticket hurting the party down the ballot.

It goes without saying that the margin in the House matters—but how much? It really comes down to the ideological diversity within the majority. If the majority party has 225 members who vote in ideological lockstep, then it doesn’t matter whether the majority party ultimately has 235, 255 or 275 votes in the House.

Ideological diversity is better understood in terms of a bell curve. On one tail of the curve are members who are more ideologically strident and represent districts that support their position: the far left or far right of the party. On the other tail of the curve are members who represent toss-up districts and who, regardless of their personal ideology, must be more careful with their votes. The vast majority of the party may be largely in ideological agreement with their more strident members but are willing to make compromises to achieve policy outcomes that protect members in toss-up districts. The difficulty governing in the House comes when the members in toss-up districts and/or the strident members are too numerous and refuse to vote for any compromise.

When the ideologically strident members refuse to compromise, we call that the John Boehner problem. When Speaker Boehner led a Republican majority with 234 members but faced a far-right flank of 25 members committed to opposing all legislation that wasn’t exactly what they wanted, it effectively limited his ability to lead the House. In the latter part of his speakership, Boehner regularly had to make compromises with the Democrats that gave the minority vastly more influence in the final legislation than they typically command.

In 2009, Democrats had 257 seats in the House and still struggled to secure 218 votes to pass the Affordable Care Act. The problem then was too many members from toss-up seats and too many members who were not as far left ideologically as the majority of their caucus. The current Democratic majority of 232 is arguably less ideologically diverse than the larger 2009 majority.

With a robust progressive agenda on the table for 2021, Democrats may face the challenge of garnering sufficient support on critical legislation from the ideologically strident members who may be reluctant to compromise.

The margin will still matter significantly if Democrats control the White House, the Senate and the House and seek to move major progressive legislation. The effort to get to 218 votes will always be a challenge. Democrats will have to meet that challenge while satisfying the vast sweep of their majority and their more ideologically strident members. Doing so will be easier if there are 255 Democrats as opposed to 245 Democrats in the House.in the aftermath of the general election, which will make the politics of that vote an event unto itself.

For more information, contact Rodney Whitlock.