Telehealth: Regulatory Questions Amid Legislative Uncertainty

McDermottPlus is pleased to bring you Regs & Eggs, a weekly Regulatory Affairs blog by Jeffrey Davis. Click here to subscribe to future blog posts.

May 16, 2024 – Where has the time gone? We have hit the one-year mark since the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). Yes, you read that correctly. One year!

One of the long-term consequences of the PHE was the shift in when and how healthcare services are delivered – and the different care options that patients now expect and rely upon. The expansion in the use of telehealth and other forms of virtual care was significant, and Congress paved the way by waiving certain Medicare restrictions that have historically been placed on telehealth. To highlight the legislative history and describe some of the regulatory challenges around telehealth going forward, I’m bringing in my colleague, Rachel Stauffer. For more on the current telehealth policy landscape, read our recent +Insight.

Although patients and providers are now used to these telehealth flexibilities, the Medicare waivers are only temporary. Congress has already acted twice to extend the waivers, most recently in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, which extended them until the end of this calendar year. Thus, starting on January 1, 2025, these waivers will disappear without further congressional action.

What does this mean? Come January, Medicare telehealth will return to a rural-only benefit, so Medicare patients will not be able to receive most telehealth services in urban areas. In addition, Medicare patients will need to come to an “originating” site – like a hospital – to receive these services and will no longer be able to receive most telehealth services from home.

Along with the “geographic and originating site” waivers, the following Medicare telehealth waivers also expire on December 31, 2024:

- Expansions to the list of eligible practitioners;

- Eligibilities for federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics;

- The provision of telehealth through audio-only telecommunications;

- The use of telehealth for a required face-to-face encounter prior to the recertification of a patient’s eligibility for hospice care; and

- The delay of the in-person visit requirement before a patient receives telemental health services.

While the future of these waivers is still unclear, Congress is now working on another extension. The House Ways & Means Committee marked up a two-year extension of all the Medicare telehealth waivers last week, and the House Energy & Commerce Committee is considering similar legislation today. However, the clock is ticking, and the Senate has yet to take up a specific piece of legislation. In an election year, legislative days (especially in August and October) are limited, and there isn’t much time to get a deal done. Stakeholders are pushing Congress to kick it into high gear. This week, in connection with the one-year anniversary of the end of the PHE, the Partnership to Advance Virtual Care held a virtual care week of action to raise awareness about the importance of extending the waivers.

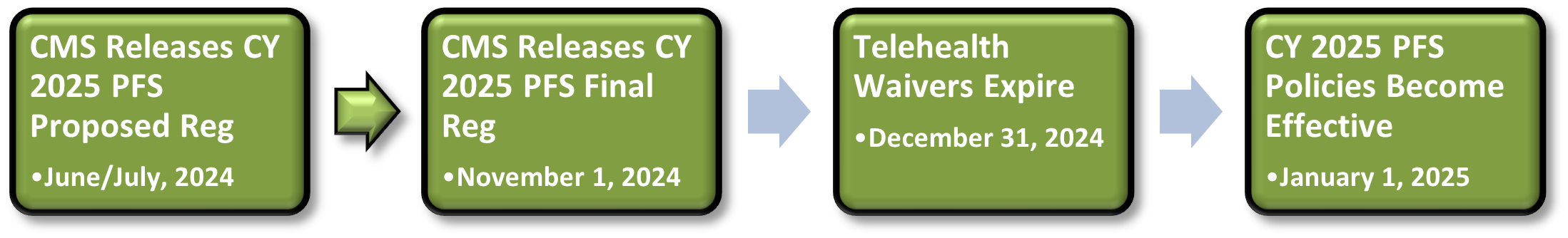

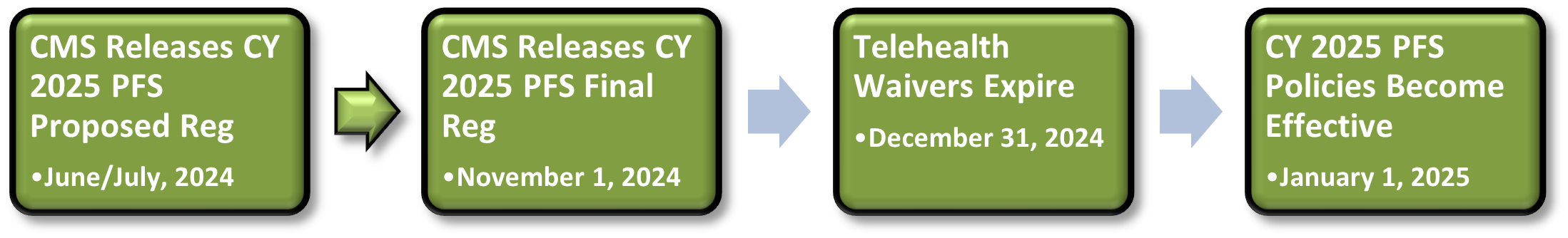

Amid this uncertainty, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must establish Medicare payment policies (including for telehealth) for calendar year (CY) 2025. CMS has typically revised telehealth policies in the Medicare physician fee schedule (PFS) annual rulemaking cycle. Every year, CMS releases a proposed reg in June or July that includes payment updates for the next calendar year. CMS then finalizes the reg on or around November 1, 60 days prior to the start of the year.

Since the official deadline for Congress to extend the waivers isn’t until December 31, CMS may go through part or all of the rulemaking process without knowing whether the waivers will be extended.

CMS can’t address the statutory limitations without legislation. CMS was clear in the CY 2024 PFS final reg that the telehealth flexibilities are only extended through the end of CY 2024 and that CMS couldn’t assume anything different. In other words, if Congress doesn’t act by June or July, CMS must assume in the CY 2025 PFS proposed reg that most telehealth flexibilities won’t exist in 2025.

Here are some possible scenarios that could occur if Congress passes legislation after the proposed reg is released:

- Legislation is passed between June/July and November 1: If Congress works out a deal after the proposed reg is released but before November 1, CMS may be unable to finalize policies that were not explicitly proposed. CMS could still, however, try to make some adjustments in the final reg to reflect the legislation and could even include a mini interim final reg in the final reg as a way to establish new policies that weren’t initially proposed.

- Legislation is not passed before November 1: If nothing happens by November 1, the policies in the final reg will become effective January 1, 2025, without accounting for the continuation of the waivers.

- Legislation is passed between November 1 and December 31: If Congress acts after CMS issues the final PFS reg (in November or December), CMS then must figure out how to address the changes quickly. CMS could issue a separate interim final reg that updates or creates new telehealth policies, but that may be difficult to accomplish before January 1, 2025, depending on when the legislation passes.

The uncertainty about whether Congress will extend the telehealth waivers (and for how long) will create numerous questions and cause confusion, especially for patients and providers. Here are some of the issues that may arise:

- What codes will be added to the permanent or provisional list of Medicare telehealth services? Although CMS did not add any new codes permanently to the Medicare telehealth list in last year’s reg, it revised the process for adding new codes to the list and created “provisional” and “permanent” lists. CMS added to the provisional list all the codes that were temporarily put on the list during the PHE but did not specify a timeline for removing them from that list. CMS stated that it would revisit provisional status through the regular annual submissions and rulemaking processes when a submission provides new evidence, when the agency’s claims monitoring shows anomalous activity or when indicated by patient safety considerations. Further, if a stakeholder wants CMS to add a code permanently to the list, the stakeholder must present supporting evidence to CMS by February 10 of the year before the policy would be effective (e.g., February 10, 2024, for CY 2025).

Since CMS’s decisions around what telehealth codes to add, delete or maintain on the permanent or provisional list are informed by evidence, it may be more difficult for CMS to conduct assessments if the data presented are based on experience from 2020 onward when the PHE waivers have been in effect. For example, would CMS consider evidence about the effectiveness of telehealth services occurring in urban areas or when the patient is located at home if the agency must assume that those flexibilities won’t exist in 2025, or will CMS have to separate and disregard or discount that evidence? Stakeholders, including providers and patients, also may have different ideas about what telehealth services should be added to the Medicare telehealth list if the services can only be provided in rural areas and for patients located at originating sites.

- What will CMS reimburse for telehealth services? Most PFS services have two rates depending on whether the service is delivered in a healthcare facility (like a hospital) or outside of a healthcare facility (like an office). The payment to the provider for the non-facility service is higher since CMS assumes that the provider bears the cost of the expenses required to deliver the service. Conversely, provider payments for services delivered in facilities are lower since CMS believes that the facility will cover the cost of these expenses. (In fact, there is a separate payment directly to the facility for these services.)During the PHE, CMS paid telehealth services at the same rate as the agency would have paid if the service were delivered in person. For example, if a primary care provider delivered a service to a patient via telehealth that would have typically been provided in person in an office setting, the provider could bill the higher non-facility rate for that service no matter where the primary care provider or patient was located. In last year’s reg, CMS phased out that policy and stated that it would start in 2024 to pay the lower facility rate for all telehealth services except when patients receive service from their home. In this case, CMS would continue paying at the higher non-facility rate. Therefore, payment levels now depend on the place of service (POS):

- POS 02, redefined as “telehealth provided other than in patient’s home.” (Descriptor: The location where health services and health-related services are provided or received, through telecommunication technology. Patient is not located in their home when receiving health services or health-related services through telecommunication technology.)

- POS 10, “telehealth provided in patient’s home.” (Descriptor: The location where health services and health-related services are provided or received through telecommunication technology. Patient is located in their home, which is a location other than a hospital or other facility where the patient receives care in a private residence, when receiving health services or health-related services through telecommunication technology.)

In this year’s reg, CMS may decide to pay at the lower facility rate for all services since CMS can’t assume that patients can continue to receive telehealth services from their homes in 2025. If CMS decides to go in that direction, what happens if Congress extends the waivers after the final reg is released and allows patients to continue receiving telehealth services from their homes? It remains unclear whether CMS could decide after the final reg has been issued to pay for those services at the higher rate.

- Will CMS adopt the 17 new telehealth codes recommended by the American Medical Association (AMA) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®)? If so, how will that impact PFS budget neutrality? In March 2023, the AMA CPT voted on 17 new evaluation and management (E/M) codes for the billing of telehealth outpatient and office visits that will be in effect starting January 1, 2025. CMS did not address these codes in last year’s reg but may decide to add them to the PFS in this year’s reg. If CMS does adopt these new codes, one major question will be the overall impact on budget neutrality. Under the PFS, CMS is forced to make an overarching adjustment to the PFS conversion factor if any new codes or modifications to existing codes would result in a change in Medicare spending of more than $20 million. The size of the budget neutrality impact and the corresponding adjustment to the conversion factor depend on how often CMS assumes that the codes in question will be billed. If CMS can’t assume that the new codes will be billed in urban areas and when patients are located at home, how will that impact CMS’s utilization assumptions? Will that impact CMS’s budget neutrality calculations and the size of the conversion factor adjustment?

- How will CMS make decisions about other telehealth flexibilities? In last year’s reg, CMS weighed in on some other telehealth flexibilities that were under its discretion to regulate. It decided to extend the following waivers through December 31, 2024, to align with the timing of the other waivers:

- Removal of frequency limitations: CMS continued its suspension of frequency limitations for certain subsequent inpatient visits, subsequent nursing facility visits, and critical care consultations furnished via Medicare telehealth.

- Direct supervision: CMS maintained its current definition of direct supervision to permit the presence and “immediate availability” of the supervising practitioner through real-time audio and visual interactive telecommunications.

- Supervision of residents in teaching settings: CMS continued to allow the teaching physician to have a virtual presence in teaching settings only in clinical instances when the service is furnished virtually (e.g., a three-way telehealth visit, with all parties in separate locations). This permits teaching physicians to have a virtual presence during the key portion of the Medicare telehealth service for which payment is sought through audio/video real-time communications technology for all residency training locations.

Since CMS may not know how long Congress plans to extend the other telehealth waivers for, will the agency extend these waivers for another year or two? CMS may wind up extending these waivers for a longer or shorter period than the other waivers are eventually extended for, creating some misalignment in the timing of all the telehealth policies.

These are just some of the questions that CMS and other stakeholders (including health policy folks like us) are grappling with as the future of telehealth policies and waivers is still very much up in the air!

Until next week, this is Jeffrey (and Rachel) saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs.

For more information, please contact Jeffrey Davis. To subscribe to Regs & Eggs, please CLICK HERE.